How drones can boost environmental and biodiversity conservation in the Philippines

Drones are becoming more and more common each year, but its latest application may be its most welcome yet: environmental conservation.

Unfortunately in the Philippines, unmanned aerial vehicles or UAVs have been mostly limited to commercial industries like construction, topographic land surveying, and even video production (including the occasional wedding).

Adoption by local environmental organizations has been slow, even if the same commercial advantages can be easily put into action in biodiversity management and nature conservation.

Here are 4 practical examples of how drones can help the Philippine environment today:

1. Create real-time maps of forest coverage

The struggle to get up-to-date data about our remaining forests is a huge consequence brought by the Philippines’ lack of regular monitoring.

The country’s total forest cover was down from 57% in 1934 to only 23% in 2010 based on a report from the Philippine Senate in 2015 – showing a 5 year data gap.

Then in 2019, the Forest Management Bureau published a similar report that also used the 23% forest cover statistic. This means we’re using outdated data that is more than 10 years old now.

If you notice the notes on the margins of the Senate report, it actually says forest cover is only or supposed to be updated every 4 years due to the “high cost of satellite imaging and ground validation.”

We don’t have updated coverage today because the scheduled data refresh for the past decade apparently did not happen, possibly due to those reasons.

This is where aerial survey drones come in.

Modern drones are powerful substitutes when satellite imaging is unavailable or too expensive. They excel in surveying large areas and gathering data that includes super high resolution photos and video, as well as geo-data like GPS, elevation, and distance. All these are valuable for nature conservation.

You can then use this data in a variety of ways:

- Tag forest boundaries to calculate overall coverage

- Differentiate forest types (ex: primary vs secondary, or lowland vs montane)

- Visually inspect imagery to find activities like logging, agriculture, and construction are happening

- Identify dominant tree species

- Regular monitoring to track the rate of growth or destruction over weeks, months, or years

- Create updated maps of regions that show land use categories

- Assess damage from forest fires

Drones may not be able to match the country-wide coverage of satellites, but can conduct environmental surveys for you at high speed with extremely cheaper costs and in more detail.

Drones can survey up to 200 hectares in a single day. This makes them well-suited to map and monitor areas such as:

- Mountain ranges with high slopes and elevation

- National parks and protected areas

- Mangrove and coastal forests

- Isolated or hard to reach environments like island groups and shallow reef environments

- Mining and quarry sites

Researchers in Malaysia used drones to map forests of the Seitu Wetland and identify mangrove species. According to their study, “Mapping based on the drone aerial photos provided unprecedented results for Setiu, and was proven to be a viable alternative to satellite-based monitoring/management of these ecosystems.”

In Panama, the Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations trained indigenous people on how to use drones to find illegal logging sites and map out their territories to get official land titles.

2. Population counts for endangered wildlife and nature

The Philippines has thousands of endemic plants and animals – including many that are now threatened with extinction.

This is essential because we often use the population of a species as an indicator of the overall environment’s health. If wildlife is decreasing, then there’s likely something going wrong in their ecosystem and habitat.

To estimate the size of animal populations, our researchers and biologists traditionally use manual counting methods. They either count each individual species they find in a location, or divide the locations into smaller areas then extrapolate for the full population.

You might already be aware that this method has a lot of limitations like:

- Manual counts are prone to human error

- Large teams are needed for large populations which creates consistency issues and increases human error

- Many species live in remote habitats that are hard to access or can take several days to travel and visit

- Observers need to have a good vantage point that has clear views and is hidden to not affect wildlife

- People tend to get tired when the count reaches the hundreds or thousands

Can a drone monitor wildlife better?

Yes.

In 2018, the Smithsonian Institute deployed a team of human observers and a drone to count the number of seabirds placed on a beach in Adelaide, South Australia.

The difference between them was astounding: the single drone was 43% to 96% more accurate than all observers combined, depending on the height and resolution of the photos it collected.

You can see a sample of the imagery captured and used by drones to identify the seabirds below:

Drones can be used the same way in the Philippines as one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots:

Yearly migratory bird counts in wetlands

Millions of birds every year migrate to us from Siberia, China, and Japan during the winter season.

Remotely piloted aircraft can easily be deployed to monitor the rise and fall of their local population when they rest in our wetlands as part of their migration. This is essential to check the health and progress made in our own wetlands over time such as the Las Pinas Paranaque Critical Habitat and Ecotourism Area (LPPCHEA) in Manila.

Monitoring the critically endangered Tamarraw

The status of the tamarraw (Bubalus mindorensis) has reached the point where its population needs to be accurately counted each year to guide conservation efforts. With the latest estimate placing it at only around 500 individuals left, it is critical to ensure all remaining populations are found.

Silent drones that can’t be spotted by wildlife can be deployed to support the annual count and cover a huge part of its remaining habitat in the 16,000 hectare Mt Iglit-Baco National Park in Mindoro that are too remote or too difficult to access by researchers.

3. Enhance reforestation with tree inventories and seedling monitoring

Planting trees is just the first, and probably the easiest step of reforestation.

The real test and where many fail is whether you can nurture the seedlings and buy enough time (and protection) for them to reach full maturity.

If you’ve been part of a reforestation program yourself, then you know that not all trees will survive. Seedlings need to be occasionally replanted to make up for this mortality rate, but to do that, you first need to know how many trees died out and exactly where they are.

The problem is, the bigger your reforestation, the more resource-heavy and time consuming it is to properly monitor. A walk through of the planting site may be enough for a small site, but what if your project covers 10 hectares? Or 100?

Aerial drones and UAVs help solve this exact problem in forestry.

By conducting an aerial survey of a site, we can use the imagery and data they capture to count trees far more efficiently than before.

This is particularly effective in open denuded areas where reforestation is done in measured plots. In this case, the software can easily find these plots and automatically identify seedlings and empty plots that need replanting.

Below is a sample of automated plant counting in the United States from PrecisionHawk:

Even in a worse case scenario where the reforestation site is not as organized or in clear view, photos and videos can be manually inspected to tag trees and areas that need attention, which is still much faster than going through an entire site on foot.

There’s also the option of just dispersing seeds with drones to plant 20,000 trees in a single day.

4. Typhoon damage assessment and crop health monitoring for agriculture

When farms and plantations are hit by floods and typhoons, a rapid survey of total damage usually needs to be done immediately either for insurance or to report for a government assistance program.

Unfortunately, measuring the amount of damage to a property and crops can take several days to weeks, or even not be possible if the land becomes unsafe due to flooding or erosion.

You also can’t easily see other types of damage, like the impact on the health of soil and crops. The crops themselves may still be standing, but they may now lack nutrients and not survive long enough to be harvested.

This is where drones help.

As soon as a typhoon passes, a single drone can be sent out and within the day complete a full damage assessment. This lets farmers get assistance quicker from government agencies and for those agencies to know how much planting materials are needed for recovery.

This is actually already being used in the Philippines today. You can see below how the United Nations and our own DENR deployed drones to assist farmers after typhoons in 2018:

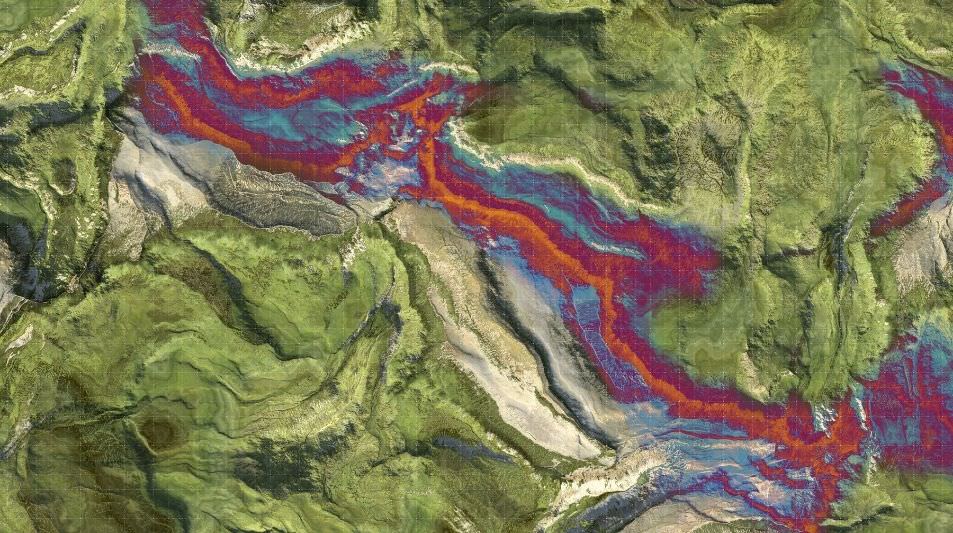

We can also equip these drones with sensors that measure near-infrared light (NIR). We use NIR to detect levels of chlorophyll in plants as an indicator of health.

A similar method is used for soil analysis using moisture levels to find dehydrated areas that need additional irrigation.

You can sample survey map below of an agricultural land from drone sensor supplier MicaSense used chlorophyll levels to detect areas with unhealthy plants (red) and healthy plants (blue).

The downside of this method is that NIR sensors are extremely expensive and the cost is hard to shoulder for small-scale farmers.

Summary: We need to mainstream drones in the Philippine environment

It’s easy to see why remotely piloted aircraft have so quickly jumped into the mainstream.

They’re cheap, need little infrastructure to operate, and have extremely flexible data gathering methods that can be applied to many industries, including for the environment.

Biodiversity and agriculture in other countries are already benefiting from drones, but adoption in environmental management in the Philippines has not yet taken off even if these are already available today.

If you know an organization that can benefit from drones, send us a message at [email protected]. We will be more than happy to give them a free demonstration as part of their projects.

Leave a comment or ask a question here: